Across Canada—and around the world—Indigenous Peoples are bearing the brunt of climate change, not because of their own emissions or consumption patterns, but because of long-standing colonial systems that continue to marginalize their rights and voices. “Climate colonialism” refers to how global climate responses, extractive economies, and market-based solutions to environmental crises reinforce colonial structures and power imbalances. These systems often lead to the exploitation of Indigenous lands and resources while ignoring or undermining Indigenous sovereignty, knowledge, and governance.

Colonialism and the Environmental Frontlines

In Canada, the legacy of settler colonialism is embedded in ongoing industrial and state projects that threaten Indigenous territories and lifeways. Although Indigenous Peoples consistently raised concerns, Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) was never fully realized, as the project moved forward without meaningful resolution or satisfaction of those concerns by the developers.

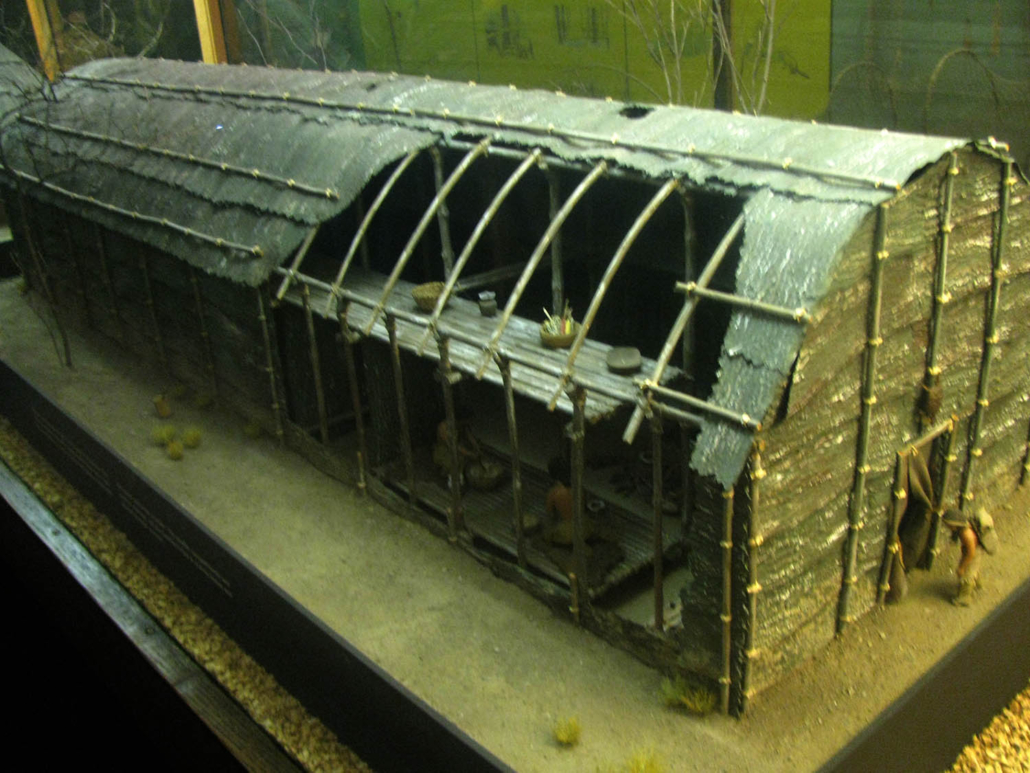

The Site C hydroelectric dam on Treaty 8 territory flooded thousands of hectares of land that are vital to the cultural and subsistence practices of the Athabaskan and Cree-speaking Peoples. Despite court challenges and community opposition, the project proceeded, highlighting the systemic disregard for Indigenous governance in energy development.

Similarly, in Alberta, the Athabasca tar sands—one of the world’s most significant industrial projects—have devastated the lands, water, and health of nearby First Nations, including the Mikisew Cree and Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation. In both cases, colonial environmental governance continues to prioritize profit and national energy agendas over Indigenous well-being and rights.

According to the Assembly of First Nations (AFN), over 120 major resource development projects are located within 200 km of First Nations communities across Canada. These projects pose ecological risks and contribute to cumulative social, economic, and health harms.

Global Parallels: Carbon Colonialism and Market Mechanisms

Climate colonialism also plays out globally through international carbon markets and finance mechanisms. Programs like REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) were initially promoted as conservation strategies to reduce global carbon emissions. However, many Indigenous Peoples in the Global South have criticized REDD+ for criminalizing traditional land use practices, restricting access to forests, and enabling land grabs under the guise of carbon offsetting.

These market-based mechanisms commodify forests and lands for their carbon sequestration potential without acknowledging the historical and cultural stewardship Indigenous Peoples have with these landscapes. A similar trend is emerging in Canada as provinces and corporations explore Nature-Based Climate Solutions and carbon offsetting projects on Indigenous lands—again, often without full community participation or consent.

A Call for Decolonial Climate Justice

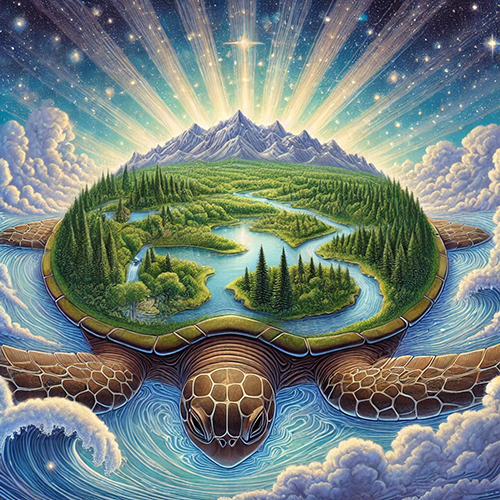

To dismantle climate colonialism, climate policy must shift from top-down, technocratic solutions to frameworks grounded in decolonial justice, Indigenous law, and local/regional community-led approaches. Indigenous Peoples are not only protectors of biodiversity and climate stewards but also inherent and treaty rights holders whose jurisdiction and authority must be recognized and respected.

Indigenous climate leadership is gaining ground through movements like Indigenous Climate Action, Idle No More, and the Land Back movement, which assert that returning land to its rightful stewards and restoring ecological and traditional governance are foundational to achieving real climate solutions. These movements challenge the extractivist logic embedded in mainstream environmentalism and offer powerful alternatives rooted in relationality, reciprocity, and responsibility to land and future generations.

Reference Points

- Assembly of First Nations, Resource Development Reports: https://www.afn.ca

- The Red Nation, The Red Deal: https://therednation.org

- Tuck, Eve and Yang, K. Wayne (2012). Decolonization is Not a Metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society.

- McGregor, Deborah (2021). Indigenous Environmental Justice and Sustainability (Various works, York University): https://profiles.laps.yorku.ca/profiles/dmcgregor/

- Indigenous Environmental Network: https://www.ienearth.org

Blog by Rye Karonhiowanen Barberstock

(Image Credit: Casey Horner, Unsplash)