Background

Are you interested in monitoring and documenting the effects of climate change in your community? Would you like to connect with and learn from other communities taking on similar projects? If so, look no further – the Indigenous Climate Monitoring Toolkit is a brand new resource created by Indigenous communities, for Indigenous communities.

Climate change is impacting Indigenous communities and ways of life across the country. Concerns range from food security and health impacts to issues with transportation, infrastructure damage from wildfires, flooding, permafrost degradation, and coastal erosion.

The Toolkit was developed to support Indigenous Peoples in Canada with planning, implementing, or expanding community-based climate monitoring projects. Communities use the data and knowledge collected to inform their adaptation planning and other decision-making.

Stories

The Toolkit includes stories shared through the eyes of those leading community-based monitoring projects, providing inspiration and guidance in hopes of encouraging others to pursue their own initiatives. Here are summaries of some of the stories to date:

Alexis Nakota Sioux Nation’s Wakâ Mne – Science and Culture Initiative

Does your community want to set up its own climate monitoring station? Click on Alexis Nakota Sioux Nation’s story to learn about their initiative to monitor climate, water quality, and greenhouse gas fluxes. Also, read about their efforts to document, archive, and share traditional knowledge to empower Indigenous culture to inform future strategies aimed at climate change adaptation and mitigation. Check out their informative video series and guides on setting up a climate station.

Does your community want to set up its own climate monitoring station? Click on Alexis Nakota Sioux Nation’s story to learn about their initiative to monitor climate, water quality, and greenhouse gas fluxes. Also, read about their efforts to document, archive, and share traditional knowledge to empower Indigenous culture to inform future strategies aimed at climate change adaptation and mitigation. Check out their informative video series and guides on setting up a climate station.

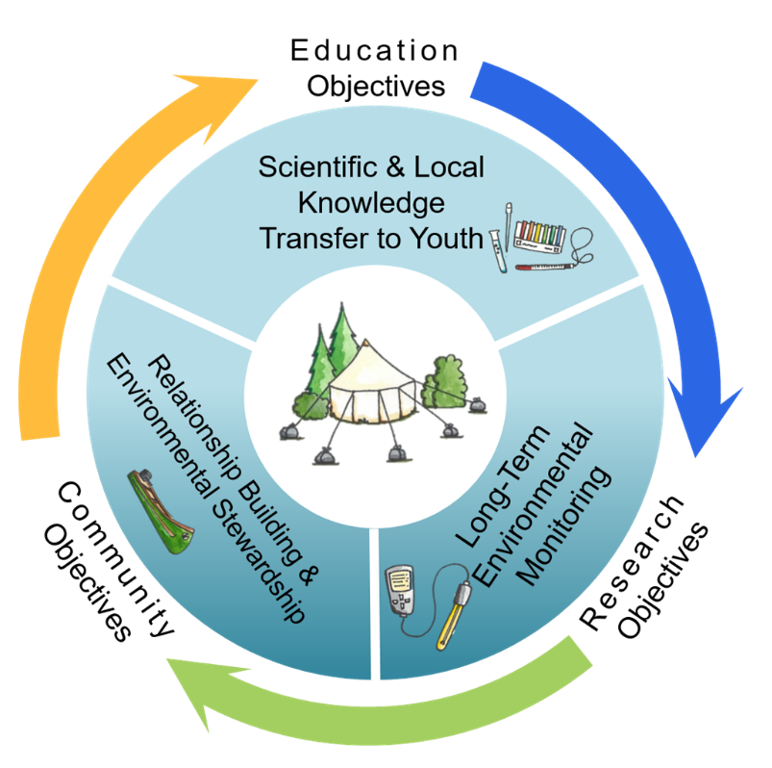

Young Hunters Program and Climate Monitoring

Are you interested in learning how to engage youth in climate monitoring? Click on the Aqqiumavvik Society’s story to learn about their Young Hunters Program. This food security initiative aims to teach kids traditional hunting practices and Inuit values and beliefs around environmental stewardship. More recently, it has incorporated monitoring aspects such as tracking changes to animals, weather, and the environment. Participants in the program gain skills and knowledge through time spent with experienced Elders and instructors by engaging in local hunting and monitoring activities. Check out their Young Hunters Manual to learn more about their program and their Community Climate Change Manual to help you implement climate change initiatives within your community.

Are you interested in learning how to engage youth in climate monitoring? Click on the Aqqiumavvik Society’s story to learn about their Young Hunters Program. This food security initiative aims to teach kids traditional hunting practices and Inuit values and beliefs around environmental stewardship. More recently, it has incorporated monitoring aspects such as tracking changes to animals, weather, and the environment. Participants in the program gain skills and knowledge through time spent with experienced Elders and instructors by engaging in local hunting and monitoring activities. Check out their Young Hunters Manual to learn more about their program and their Community Climate Change Manual to help you implement climate change initiatives within your community.

Dehcho AAROM: Indigenous-led Monitoring and Stewardship

Are you concerned about the impacts of climate change on water quality and fish? Click on Dehcho First Nations’ story to learn how their Aboriginal Aquatic Resource and Oceans Management (AAROM) Program has created a regionally administered, community-based monitoring initiative. This story covers the importance of partnerships to increase funding opportunities and capacity, practical tips on data management and field work, and the opportunities and benefits of developing a successful community-based monitoring program. Check out their hands-on case studies and water quality monitoring videos.

Are you concerned about the impacts of climate change on water quality and fish? Click on Dehcho First Nations’ story to learn how their Aboriginal Aquatic Resource and Oceans Management (AAROM) Program has created a regionally administered, community-based monitoring initiative. This story covers the importance of partnerships to increase funding opportunities and capacity, practical tips on data management and field work, and the opportunities and benefits of developing a successful community-based monitoring program. Check out their hands-on case studies and water quality monitoring videos.

Discover More

Beyond providing you with stories from leading community-based monitoring projects, the Toolkit provides an easy to navigate Resources tab equipping you with links to key resources related to climate monitoring and adaptation, as well as a Steps tab with step-by-step guidance to plan, design, and implement your project.

In addition, check out the interactive map to see some of the Indigenous-led climate monitoring related projects that have taken place or are ongoing across Canada.

Visit the Toolkit today to get inspired, start your own project journey, or share your own story and resources with your peers.

By First Peoples Group and the Indigenous Community-Based Climate Monitoring Program at Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada

(Photo credit – header photo: Lesly Derksen, Unsplash)