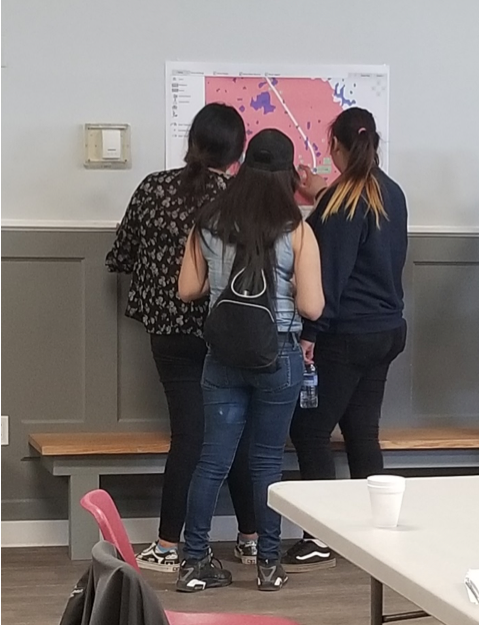

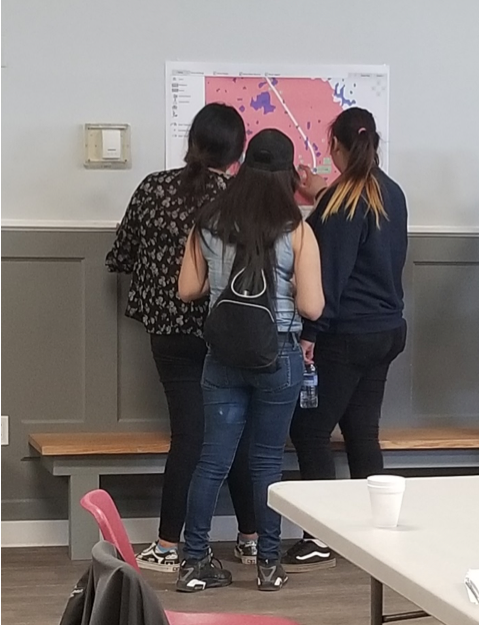

(Image: Researchers and community members looking at maps of flooding events in YQFN)

Introduction:

Being no stranger to threats from climate change through growing up with constant flooding, forest fires, and extreme weather overwhelming his community, Myron Neapetung, a Councilor at Yellow Quill First Nation, had an idea to help his community be better prepared for the future. Over the years, he had built relationships with the University of Saskatchewan, and felt like it was time to start gathering the Elders’ stories and working with scientists on climate change concerns so that ongoing problems could finally be resolved. In May 2018, together with Lori Bradford, an Assistant Professor in the School of Environment and Sustainability at the University of Saskatchewan, Myron launched a First Nations Adapt Program grant to look at their community’s vulnerability to more frequent flooding brought on by the effects of the climate emergency.

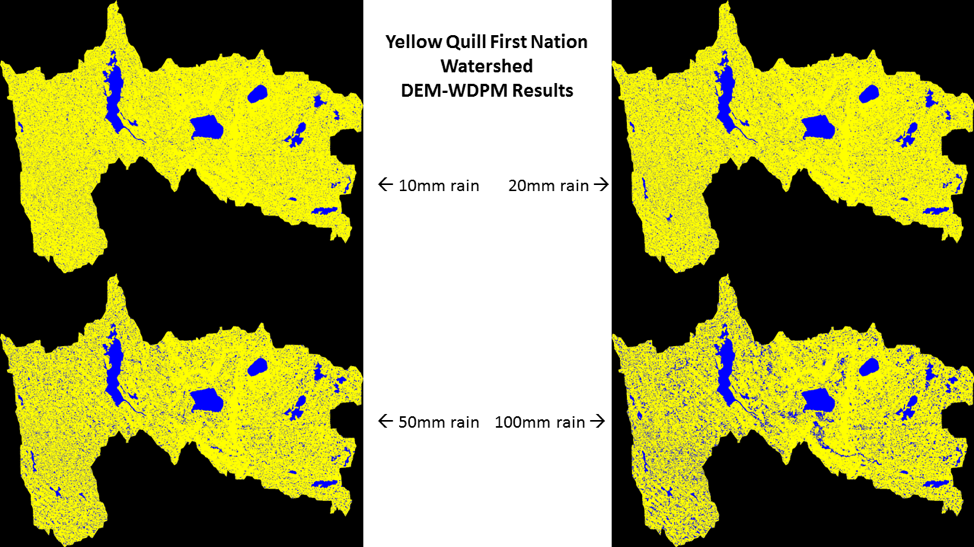

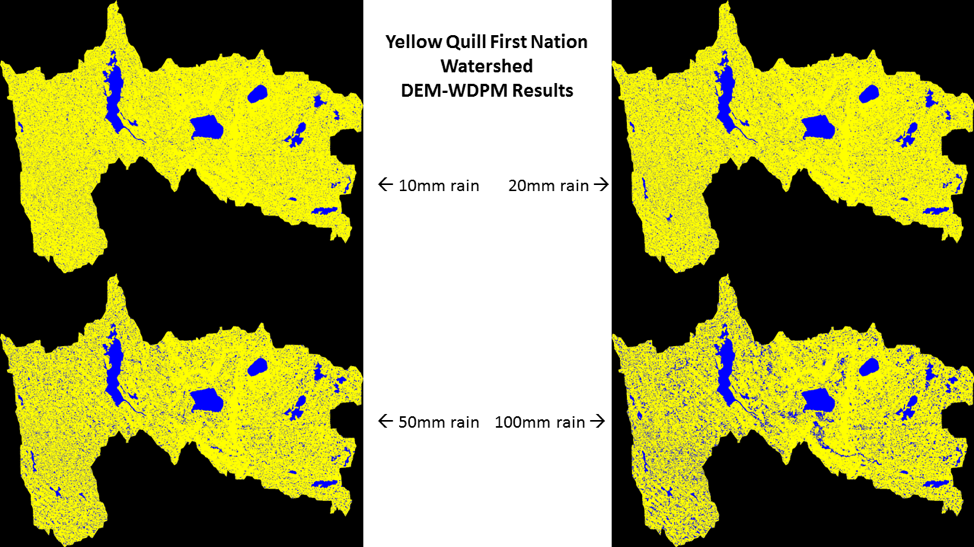

The project had four main parts. Looking back through records at the Band office, and the urban services office in Saskatoon, Myron realized that the community was short on record keeping and mapping capacities, so the first step was to contract LiDAR services (Light Detection and Ranging, a remote sensing method that uses a pulsed laser to measure ranges) for the entire watershed. With this very detailed information about the elevation of the land around the reserve, computer modelers at the University of Saskatchewan were able to put together risk maps and put these maps into models that predict flooding. The community was presented with maps that showed where water would likely go if there were a variety of storms, like 50- and 100mm flooding events. Elders and knowledge holders in the community verified these maps to help the computer modelers improve their accuracy. With a shortage of LIDAR available in Saskatchewan, the University-based modelers were very grateful to be involved in this work and learning from those experiencing flooding was incredibly valuable to them.

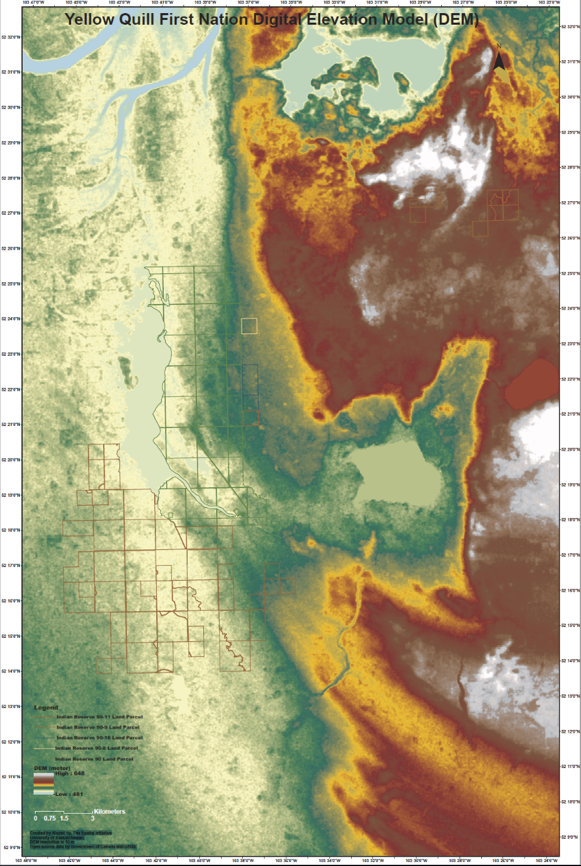

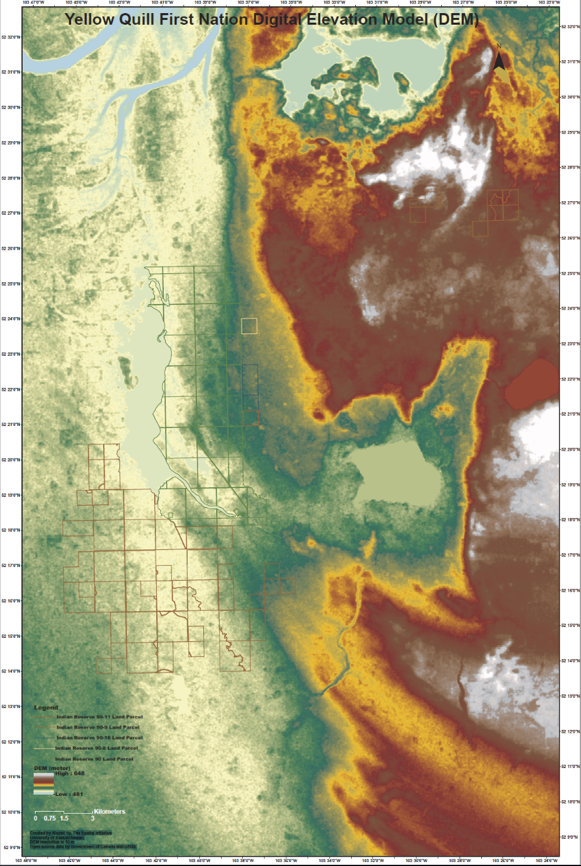

Picture 1: LIDAR DEM Map showing elevation

The second step involved bringing people, young and old, from the community together to talk about flooding. That involved many community meetings in the summer of 2018, interviews with Elders and knowledge holders, projects with school students, and sharing circles. We also used a variety of other data gathering techniques like drawing and taking pictures of flood effects, going on extensive community tours, hosting poster sessions for feedback on any information gathered already, and enjoying many community lunches together. Myron, University students, and the researchers then analyzed the combined data from these activities and made posters and presentations to share with the community and other researchers at conferences.

Picture 2: Community meeting with posters

The third step involved hiring three summer students in the community to look at the emergency management planning documents, and talk with emergency personnel, such as firefighters, road crews, water treatment officers, Chief and Council members, health care workers, wellness center staff, and others involved during emergencies. These students catalogued everyone’s ideas to improve emergency plans in the case of flooding. The three summer students are in the middle of summarizing their results and comparing them to what is written in the official documents.

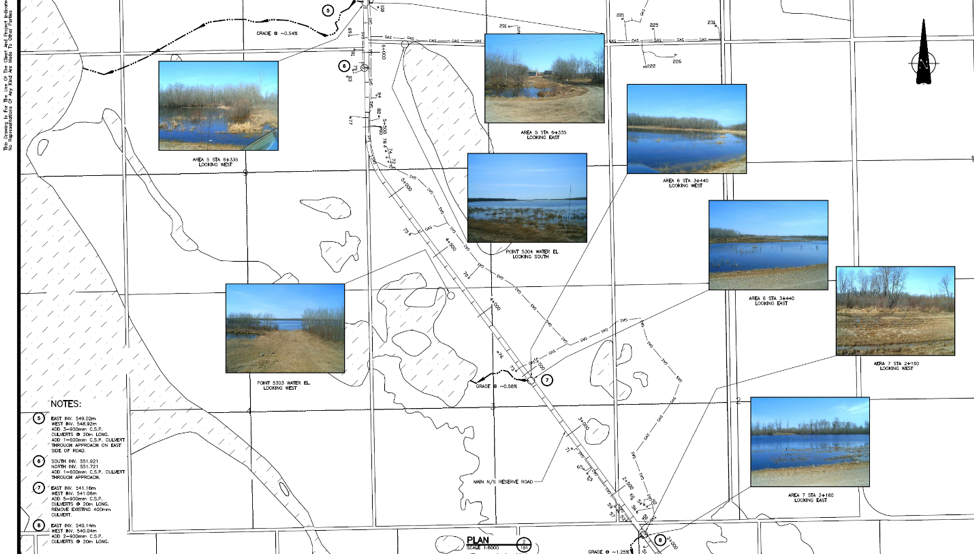

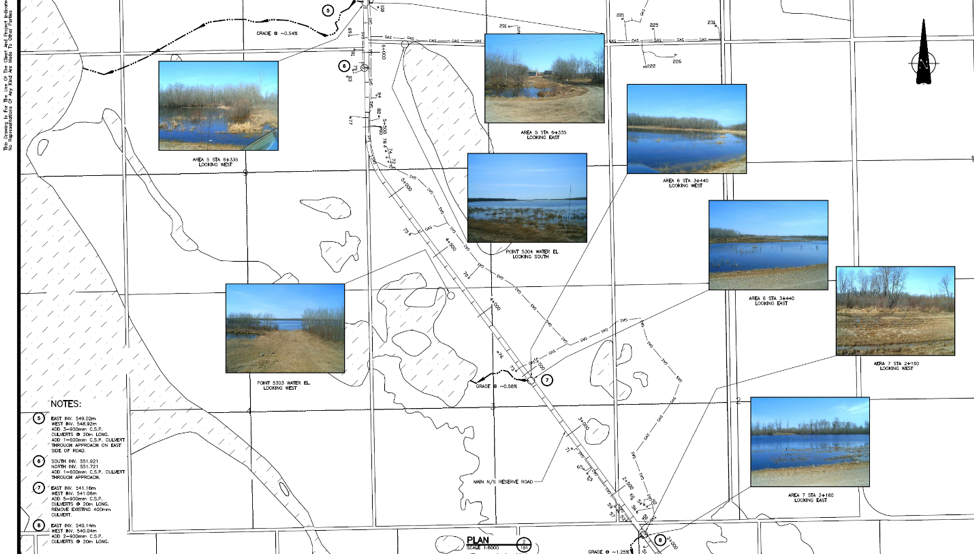

Picture 3: Photo of records of previous work on flood engineering

The last step for the vulnerability assessment was to invite some engineering experts to do an infrastructure assessment in the community to give a thorough review of important infrastructure that is at risk from ongoing flooding. The First Nation PIEVC Infrastructure Resilience Toolkit process will be occurring August 19-23rd in Yellow Quill with the assistance of the Ontario First Nations Technical Services Cooperative, Stantec Inc., and the Saskatchewan First Nations Technical Services Co-operative.

Picture 4: Where the water will go for certain flood events

The overall goal is to learn about the vulnerabilities of Yellow Quill First Nation so informed decisions about how to prepare for a future of unpredictable climate-related challenges can be made in a way that respects community-held knowledge and experience while also harnessing some of the hydrological modelling sciences to predict how climate change might affect daily life. This first climate change adaptation opportunity has spearheaded YQFN’s involvement in a number of research projects around water at the University of Saskatchewan and farther afield in Canada, and has provided a lot of capacity building opportunities for people from Yellow Quill to learn more about climate change, floods, research, and emergency management.

Authors: Myron Neapetung, Yellow Quill First Nation and Lori Bradford, University of Saskatchewan