As an Indigenous geography scholar and researcher, I increasingly focus on the realities of climate change and its profound impact on ecology. In a recent class I co-instructed at the Queen’s University School of Urban and Regional Planning, I introduced students to ancestral Indigenous planning, centring on a 12th-century Iroquoian community model. The discussion illuminated how human interactions with the land and natural resources were determinants of community planning and fundamental to sustaining the delicate balance of human and non-human relations.

Exploring the interrelationship of people and place through the cultural geography of the Haudenosaunee, we delved into how identity itself is shaped by land and its natural actors. For a class filled with aspiring urban and regional planners—along with three practicing city planners—the experience was transformative. It quickly became apparent that planning must move beyond rigid zoning practices and embrace place-based autonomy, where decision-making aligns with the rhythms and needs of the land itself.

Haudenosaunee Knowledge and Climate Adaptation

The prevailing mindset in modern urban and regional planning has long been dictated by frameworks rooted in industrialization, urban sprawl, and resource extraction. Much of the profession adheres to highly regulated, standardized practices that prioritize short-term economic gain over long-term environmental sustainability. Yet Indigenous planning offers a profound alternative that considers the interconnectedness of people, land, and ecological cycles.

This perspective challenges the conventional notion that humans design space for habitation; instead, it asserts that we must enhance and harmonize with the natural rhythms of place. When we examined Haudenosaunee planning principles, students responded with genuine curiosity and awe. Concepts such as ensuring the autonomy of water sources were central to settlement adaptation, using topography for protection, and identifying prime lands for cultivation were revelatory for many.

The more students engaged with this knowledge, the more they recognized that contemporary urban and regional planning must evolve to address the growing need for sustainable living. Climate change is no longer a future concern—it is here and reshaping our landscapes. If planners and policymakers fail to integrate climate adaptation and Indigenous value systems into their frameworks, they risk perpetuating unsustainable models that continue to degrade the environment.

The Iroquoian Longhouse: A Model for Sustainable Design

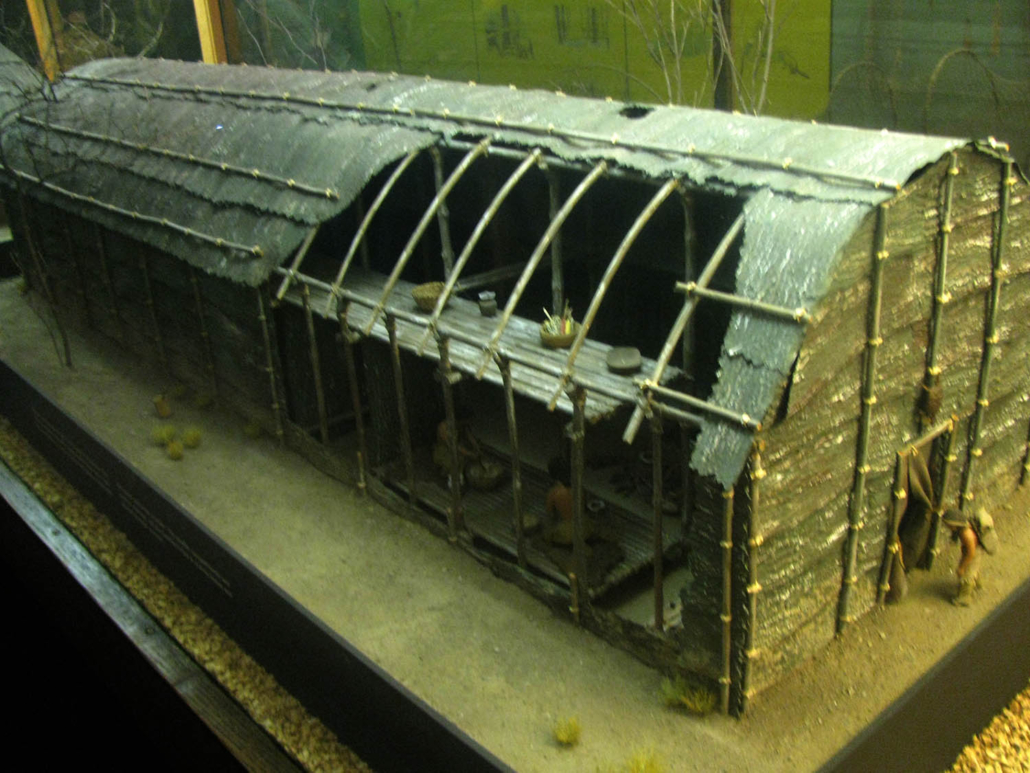

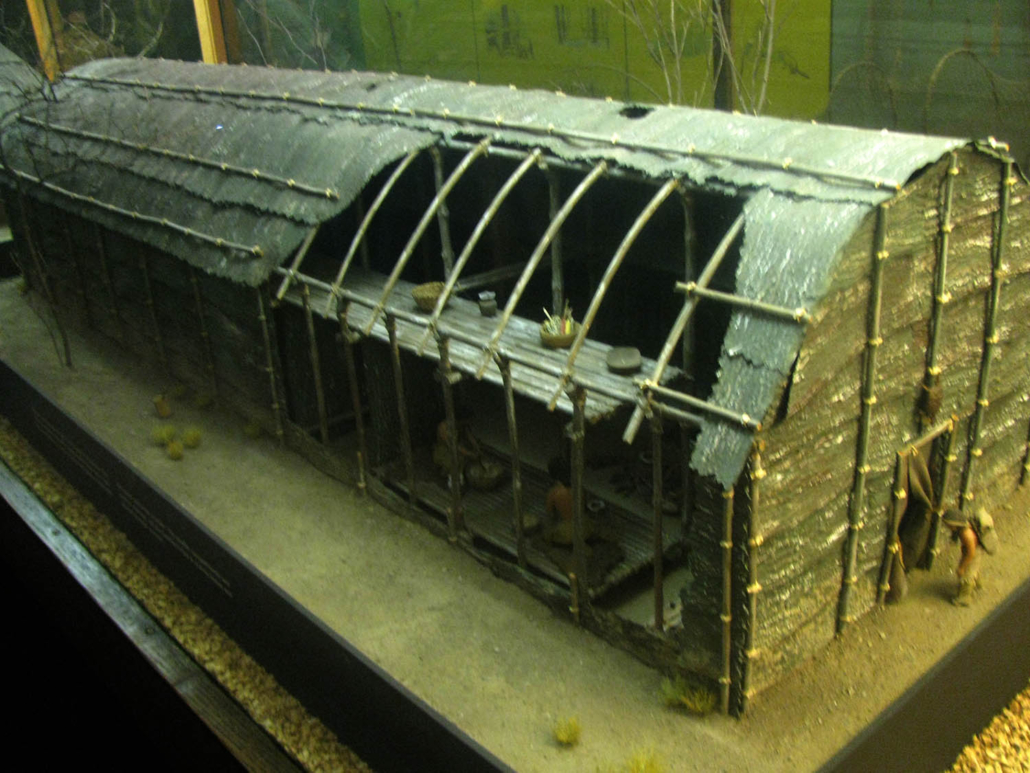

A compelling example of Indigenous planning is the Iroquoian longhouse, a structure that served as both shelter and a communal space. Built from natural materials such as elm bark, the longhouse was constructed with deep respect for the land—only taking what was necessary, ensuring sustainability, and allowing trees to replenish. The longhouse’s design reflected a life-cycle systems approach; structures were built for 30 to 40 years before being returned to the earth, where they naturally decomposed and reintegrated into the landscape.

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons (‘Exterior View of Traditional Iroquois Longhouse’).

The students were fascinated by the idea that communal spaces were designed with a finite yet renewable existence. In contrast, modern urban development often prioritizes permanence and expansion, creating structures that outlive their usefulness, contributing to urban decay and environmental strain. What if, instead, our urban centers were designed with adaptability in mind? What if materials used in construction aligned with ecological cycles rather than being treated as disposable waste?

The Power of Education in Transforming Urban Planning

Education systems are critical in fostering openness to new ideas and methodologies. However, much of the current urban planning curriculum is rooted in post-war suburban development models emphasizing efficiency, uniformity, and mass production. Integrating Indigenous value systems, environmental determinants, and climate change considerations into planning education is essential in fostering a holistic, future-focused approach to community development.

The challenge, of course, lies in decolonizing the profession itself. Innovation in urban and regional planning is often stifled in favour of “tried and true” practices prioritizing economic stability over ecological well-being. Yet, if planners are to truly serve the needs of future generations, they must expand their thinking beyond conventional models. Indigenous planning philosophies, such as those practiced by the Haudenosaunee, represent just one of the hundreds of cultural contributions that can help reshape human-centred design into more inclusive and regenerative.

A Call to Action: Expanding Thought, Embracing Change

If climate change is to be effectively addressed in community development, it must be at the forefront of planning discussions, not an afterthought. Recognizing the significance of place-based planning, environmental stewardship, and Indigenous knowledge systems is not an elective enhancement but a necessary revolution.

Urban and regional planning must evolve beyond rigid regulations and embrace the knowledge that has sustained Indigenous communities for millennia. The interconnectedness of land, water, climate, and human habitation must become central to planning efforts. This requires an intentional shift in education that welcomes new perspectives, cultural inclusivity, and Indigenous methodologies as fundamental learning components. It is not merely about integrating Indigenous knowledge for inclusion but about recognizing its profound value in creating sustainable, resilient, and thriving communities.

In the face of climate change, the question is no longer whether we need change but whether we are willing to embrace it. The wisdom of Indigenous planning offers a pathway forward, one rooted in reciprocity, sustainability, and deep respect for the land. Now is the time to expand our thinking, decolonize our approaches, and integrate climate consciousness into planning.

For the future of our communities, ecosystems, and generations, we must choose transformation over stagnation, reciprocity over exploitation, and sustainability over short-term convenience.

– By Rye Karonhiwanen Barberstock

(Header Image Credit: A.C., Licenced, Unsplash+)